This article is written about an incident that occurred in 1940 overhead New Milton and ended in Milford on Sea. It was written by Derek Jones at the request of the Milford on Sea Historical Records Society. Owing to the length of the article it was not possible to publish the article in their magazine and so is reproduced, in full, on the MHS website.

Derek is still researching this wartime incident that is now part of our local history. He would be very interested to hear from anyone who witnessed the incident or who has information that can add to the full account of the events. Derek can be contacted via our contact page here.

This article is copyright Derek Jones 2020.

Updated 5 July 2020.

609 Squadron joins the “Century Club”

21 October 1940

Introduction

In common with many other villages, towns and cities across the country during the Second World War, Milford on Sea suffered its fair share of hardship and loss. Many sons and daughters of the village were caught up in the horrors of conflict, some never to return. During the war years, the village played host to many “visitors”, in various guises, some to convalesce, some standing by ready to repel an imminent invasion from across the Channel and many in preparation for an invasion of our own into occupied Europe. The latter in the hope that this action, however costly, would bring the war to an end, and to bring loved ones back home.

However, this account of an incident in the Autumn of 1940 recalls “visitors” of a quite different kind. Visitors, whose very presence in the village would challenge the very fabric of society, questioning our ability to forgive those who have inflicted such harm, but equally showing our compassion in the face of loss. I refer to the crash of a German aircraft in area of Blackbush on the 21st of October 1940.

A full minute by minute record of the occurrence is not possible due to the absence of detailed records and the loss of eyewitness to the passage of time. The information that follows has been obtained from Royal Air Force and Luftwaffe reports, local newspapers, eyewitness accounts, local history records and the notes made by an aviation historian, the late Peter Foote, who had previously researched the aircraft and crash site. It reflects the best possible account of the last flight of the Junkers 88 and its crew given the all the available information at the time of writing.

Unlike the Junkers 188 which crashed near Exbury in the New Forest[2] later in the war, there is no mystery here, only an account of several young airmen and five civilians all doing their duty, all of whom were eventually to die in the service of their respective countries.

Eighty years have passed since this incident and the world has change beyond comprehension, we are now a much more open, tolerant and inclusive society, and so, in writing this account it should be recognized that there is no intention here to glorify war, nor to vilify any of the participants. This article seeks of capture a moment in time and act as a reminder for us all that in war there are no winners.

We will remember them

Derek Jones

March 2020.

Setting the scene

Despite a plethora of research material and published works on the subject, there is much debate regarding the exact dates the Battle of Britain took place, but the consensus appears to be 10th July to the 31st October 1940. However, much less is recorded about the latter stages of the battle. “Battle of Britain Day”, the 15th September 1940 is widely regarded as the turning point in the air war with 185 German aircraft reportedly destroyed.[3] The 17th of September is recorded as the day that Hitler postponed “Operation Sealion” (the planned invasion of England) indefinitely. So, one could be forgiven for believing that the 17th of September was the end of the battle.

It is, however, unlikely that the aircrew on both sides of the campaign would have considered that date to be the end. The German assessment of the situation was grave, “The British have used the breathing space (because of bad weather) to strengthen their fighter force with pilots from flights schools and new material from their factories, including aircraft that have not yet been painted. Thus, the enemy air force was greatly reinforced. The British engaged the German bomber units with less well-trained fighter squadrons, with several cases of deliberate ramming as a last resort. Meanwhile German fighters came under attack from better trained British Fighter pilots.”[4]

In response to the perceived growing strength of the Royal Air Force, on the 20th of September 1940 Luftwaffe Reichsmarshall Herman Göring, issued three new directives;

- From now on, major attacks in daylight will only be carried out by small formations of bombers, not more than the size of one Gruppe, escorted by strong formations of fighters and Zerstörer units.

- Individual bomber crews shall carry out nuisance raids using clouds as protection from fighter attacks. The targets of these nuisance raids are London and industrial targets in other cities.

- The bomber offensive on England is to be mainly shifted to the hours of darkness.

Directive two would have a direct impact on the crew of a Junkers 88 coded 9K+BH who would lose their lives in Milford on Sea only a month later.

In the change of tactics, industrial sites were to be targeted, specifically including factories producing aircraft and aircraft engines. Sites such as the Gloucester Aircraft Factory at Brockworth and the Supermarine factory in Southampton were deemed of particular interest. Special crews known as “destruction crews” were selected for these missions. These crews were selected for their skill and previous achievements. Each crew was allocated a specific target with the final decision of when to attack and under what conditions being left with the captain of the aircraft. These crews relied only on their own knowledge and skills as the missions were conducted without any fighter escort. The nature of their task and the fact that they had no fighter protection meant that missions were extremely hazardous.

The Gloucester Aircraft Company.

The Gloucestershire Aircraft Company was born out of necessity in 1917, originally to produce parts and later aircraft to support the war effort. By 1918, the GAC was producing forty-five aircraft a week.[5]

The interwar years were lean times for the company, but they secured contracts overseas notably for the Imperial Japanese Navy and the New Zealand Air Force and of course at home for the Royal Air Force. The company also designed and constructed aircraft with civil use in mind, producing several designs that would impact greatly in aviation racing circles.

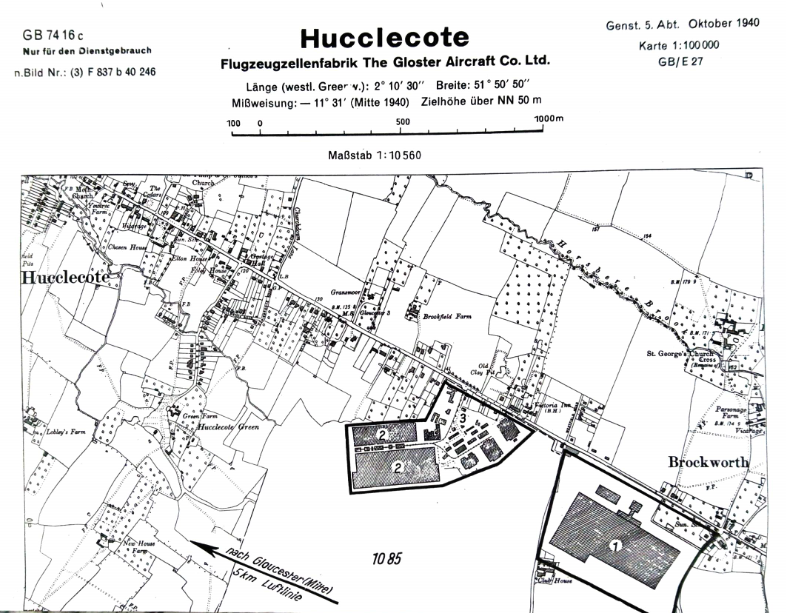

In 1925, increased production and a requirement for greater workshop space necessitated a move of premises from Sunningend to Hucclecote. By this time the company has a growing international reputation for quality. However, due the difficulty many overseas customers had in pronouncing Gloucestershire, in 1926 the company shortened its name to the Gloucester Aircraft Company. Many employees simply referred to it as GAC, a term of endearment which endured.

In the late 1930’s with the clouds of war once again gathering over Europe the GAC turned its full attention to production of aircraft for the Royal Air Force.

To provide some context to the Luftwaffe interest in the Hucclecote site, the GAC was one of the main sites responsible for production of the RAF’s Hawker Hurricane, with over 1000 built and in service by October 1940, many of which saw service during the Battle of France and later the Battle of Britain.[6] The Luftwaffe’s interest in the site however, predated the mass construction of the Hurricane. Luftwaffe aerial reconnaissance photographs and maps of the Gloucester area that were recovered post war show dates of 1939 and earlier.

The example below held in the Gloucester archives is date marked 5th October 1940.

The war effort at the GAC received the Royal seal of approval when the site hosted a visit by King George VI and Queen Elizabeth on 10th February 1940. This was to be the second war time Royal visit to the site. In 1917, King George V and Queen Mary also visited to inspect the GAC’s efforts to support the war in Europe.[8]

The first indication that the Luftwaffe was to take an interest in the GAC occurred on the 25th July 1940, Pilot Officer Charles ‘Alec’ Bird was at Kemble airfield in Gloucestershire when a Junkers 88 (9K+GN) of 5 Kampfgeswader 51 passed overhead, bound for the GAC. Bird and another pilot officer, both members of 4 Ferry Pilots Pools, scrambled and intercepted the raider. Bird reached the German first, opened fire, and closed for another attack. It is not clear from records but Bird then either rammed or collided with the German aircraft. The Junkers crashed at Oakridge, all but one of the crew being captured. Pilot Officer Bird lay dead in the wreckage of his Hurricane nearby. Sadly because 4 Ferry Pilots Pool was not one of the accredited Battle of Britain units, although Pilot Officer Bird was lost in action between the campaign’s official dates, he is not considered one of ‘The Few’.

The Luftwaffe raids brought death to the site on two occasions, first on 21st October 1940, the details of which we will explore further later in this publication and again on Easter Sunday, the 4th April 1942. On that occasion eighteen people were killed, three of them children with a further 200 people injured and damage to about 200 buildings. Despite the high loss in terms of human life, production of the Hawker Hurricane was not halted by either raid.[10]

Monday 21st October 1940

Monday the 21st of October 1940 was recorded as being a dull Grey day, mainly cloudy with fog and intermittent rain causing poor visibility over England.[11] Ideal conditions for the lone German medium bomber, a Junkers 88 (Ju88) belonging to Kampfgeswader 51 (Bomber Wing 51), which took off from Melun Villeroche, an airfield located 21 miles southeast of Paris. The Ju88 contained four Luftwaffe crewmen the equivalent in rank of a Lieutenant, two corporals and an aircraftman. Their task, to locate and destroy the Gloucester Aircraft Factory to prevent or at least delay the construction and supply of Hurricane fighters for the Royal Air Force, in the hope that once again the Luftwaffe could regain superiority of numbers in the air.

The first known contact with the bomber was at 12.55 over Portsmouth when the Royal Observer Corps (ROC) noted; “Raid 45 in Q22 NW heard at 6000” feet[13]. Eleven minutes later an entry in the ROC logbook 21 of Group 3 read; “13.06 Boscombe Down warned that Raid 45 in U86”, indicating that the aircraft was on a north westerly heading, on a direct route for Gloucester.

A local man Colonel, Sir James L. Sleeman, C.B., C.M.G., C.B.E., M.V.O. (Commandant of the Gloucestershire Special Constabulary) recounts; “at 1.25p.m. when motoring with my wife towards Brockworth Aircraft factory, we heard terrific explosions and saw a low-flying enemy plane making out towards Painswick; great clouds of smoke and dust rising from the factory. Although so sudden and unexpected, its pilot had ample time for deliberate aim, he had fortunately so miscalculated that only one bomb fell upon the factory. Had he released his load a few seconds earlier, great havoc must have been occasioned, for the aeroplane had traversed the entire length of an enormous and important constructional block, as it was, some thirty casualties resulted, and I was there to see (in my other capacity as a Chief Commissioner of St. John) these being effectively dealt with by a St. John first-aid party under Supt Clutterbuck.”[14]

The target had of course been The Gloucester Aircraft Factory, Brockworth, the airfield being located some half a mile south of the village. The lone bomber dropped three High Explosive (HE) bombs all of which fell harmlessly in nearby fields. However, an oil bomb fell on the roof of No. 7 Machine Shop causing the casualties and damage described by Colonel Sleeman above.

The air raid reports for the area record little detail of the incident:

Air Raid Bulletin No 26 – On Monday October 21st, 1940, Air Raid message yellow from control received 13.25hrs. Several large explosions were heard from the direction of Brockworth at 13.24 hrs & smoke issuing from the direction of the aerodrome. One oil bomb hit a building causing some casualties from burns, three HE dropped in fields & did no damage. Air Raid message white received 13.45.[15]

It would appear that little or no warning of the raid was given. Local witnesses corroborate that account; “I lived opposite No.2 gate of the factory and was about to return after my staff dinner time, it was approx. 1.45 pm, the bombs dropped, I was told one was on the tool room, many people were injured. Then the siren went off and the barrage balloon went up”.[16]

“Riding my bike along Hucclecote Road, I heard an unusual drone coming from an aeroplane. Looking up I saw 5 or 6 black sticks fall out of the plane. I heard some loud bangs. There being no T.V. and very few phones, we heard by word of mouth what had occurred – the GAC had been bombed!”[17]

Another local resident Philip Bridgeman recalls “One day in the Autumn of 1940 there had been a “red alert” all morning and all clear sounded around lunch time. A gang of workmen were working in a roof bay over the tool room at GAC installing the new sliding black-out gear. Just before the break the foreman moved all but two, George Newman and Dick Wallace, to start on the higher bays over the erection shop. We had only just returned after the break at about 1.30pm when, a medium sized aircraft slipped out of the clouds over Cooper’s Hill and with motors shut back spiralled silently down over Brockworth and let go a stick of bombs from about over the Victoria Inn, from what looked no more than three to four feet, its tail and wing markings clearly visible.

Never was accurate identification more vital, for the JU88 was recognised at some distance from off the roof, giving just time for those on the erection shop roof to slide down from their perch on the shallow pitched glazing lights and on to the more substantial cat-walk below, and hang on for dear life as glass and asbestos were shattered by the blast.

The tool room received the direct strike with several deaths and numerous casualties. George Newman was killed, Dick Wallace was severely burned by the oil bomb which had obviously been intended for the dope shop and its highly inflammable content, where many women were employed. Had it struck where intended the result would not bear thinking about. As it was, the result was minimised to some extent by a large steel roof joist taking the first impact so that the main blast and fire-spread was at roof level rather than ground.

From an operational point of view the Luftwaffe “fluffed” it. It is not certain if one of the H.E.’s (High Explosive bombs) actually hit the buildings, two missed altogether, and never in the course of the war could a target have been so wide open to attack.” [18]

Five employees perished as a result of the bombing at the factory on the 21st October 1940:

Wallace Frederick Fryer was born on the 24th May 1902 in Cam, Gloucestershire. On the 3rd of August 1925 Wallace married Effie Young at Dursley Parish Church. The couple made their home at Cintra, Uley Road, Dursley. Wallace secured work at the GAC as a Toolmaker. He died at Gloucester Royal Infirmary on the 23rd of October 1940, as a result of wounds sustained on the 21st, aged 38.

Charles Edward Lowe was born on the 27th April 1896, he lived at 15 Leckhampton View, Shurdington near Cheltenham with his wife Mable and their five children. Charles was employed as a General Labourer at the GAC and was in the tool-shop when the raid began. He died at the scene aged 46. Charles is buried at St Paul’s Church burial ground, Shurdington.

Charles Edward Lowe was born on the 27th April 1896, he lived at 15 Leckhampton View, Shurdington near Cheltenham with his wife Mable and their five children. Charles was employed as a General Labourer at the GAC and was in the tool-shop when the raid began. He died at the scene aged 46. Charles is buried at St Paul’s Church burial ground, Shurdington.

George Charles Henry Newman was born on the 6th October 1920. He lived with his parents and sister at 19 Sweetbriar Street, Gloucester. A Carpenter by trade, George found employment at the GAC.

[20]George was working on the roof when the bombs fell. He was fatally injured but was taken to the Gloucester Royal Infirmary. His father Jack, reached the hospital in time to hear his final words; “I am a wounded soldier now”, he died a few moments later aged just 20.[21] George’s funeral was conducted on the 26th October at St. Mark’s Church, Gloucester. The mourners included, his parents, his fiancée Kathleen Dashwood, and his workmate Philip Bridgeman, whose account of the incident appears above. George seen here on the left.

[20]George was working on the roof when the bombs fell. He was fatally injured but was taken to the Gloucester Royal Infirmary. His father Jack, reached the hospital in time to hear his final words; “I am a wounded soldier now”, he died a few moments later aged just 20.[21] George’s funeral was conducted on the 26th October at St. Mark’s Church, Gloucester. The mourners included, his parents, his fiancée Kathleen Dashwood, and his workmate Philip Bridgeman, whose account of the incident appears above. George seen here on the left.

Alexander Anthony Christopher Smith was a member of the Home Guard, he was fatally injured during the raid and died at the Gloucester Royal Infirmary as a result of his wounds on the 23rd of October 1940.

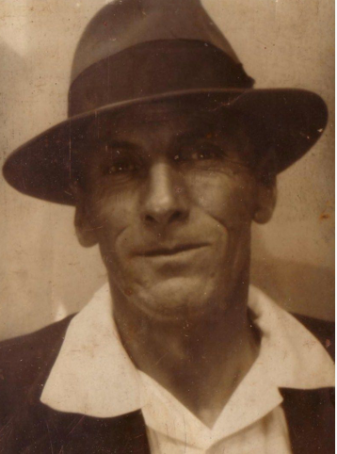

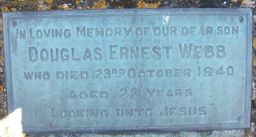

[22]Douglas Ernest Webb was born on the 30th October 1918, he was the son of Ernest and Mabel Webb of Combend Manor, Elkstone near Cheltenham. Douglas worked as a Toolmaker at the GAC and died of wounds on the 23rd of October 1940 at the Gloucester Royal Infirmary aged 21.

[22]Douglas Ernest Webb was born on the 30th October 1918, he was the son of Ernest and Mabel Webb of Combend Manor, Elkstone near Cheltenham. Douglas worked as a Toolmaker at the GAC and died of wounds on the 23rd of October 1940 at the Gloucester Royal Infirmary aged 21.

As bad as this was, there was worse to come for the Gloucester Aircraft Factory. On the 6th of April 1942, six bombs were dropped, one of which fell on a crowded car park killing eighteen people, three of whom were children, another two hundred people were injured.[23]

The raid of October 1940 gave rise to many questions. If the Gloucester Aircraft Company was so important to the war effort why were there no anti-aircraft artillery units in the area? There were also several inevitable rumours surrounding the raid. One such rumour was that the Germans had a spy in Cranham Woods which overlooked the area in which the factory was located. This was because the JU88 attacked just as the anti-aircraft balloons were being lowered. This rumour was never substantiated but lingered on in the memory of locals for many years.

“I was a nine-year-old boy standing at the gate of my home in Beaufort Road, Gloucetser. It was between 12.30 and 2.00pm on that day, the all clear siren had sounded a few minutes previously and the barrage balloons were being winched down. A few minutes after the balloons were down, I saw a plane dive out of the clouds towards, what I found out later was, Brockworth.”[24]

“The German plane dived from the clouds in quite a steep dive approximately 5-10 minutes after the all clear had sounded. The sirens used to sound regularly over Gloucester, mainly at night, we often heard German planes flying over on their way to Birmingham or Coventry.”[25]

Barrage balloons were designed to force the enemy planes to climb higher over specific targets thus making aerial bombardment less accurate and ultimately saving the target from suffering a greater degree of damage, the so called “roof over Britain”. The first balloons were sited in and around London in 1937 and by 1938 the order was given to increase the balloon establishment across the country specifically in the major cities of Birmingham, Bristol, Manchester, Liverpool, Hull, Newcastle, Plymouth, Southampton, Glasgow, and Cardiff

In August 1939, the No 11 Balloon Centre was established at Pucklechurch. In June of the following year 912 Squadron was established at Pucklechurch to protect the Gloucester Aircraft Factory. By the time of this incident on the 21st October, 24 balloons were installed at the GAC and were fully operational.[26] It is testament to the importance placed on the site that the cities of Southampton and Portsmouth had 50 (inc 10 waterborne balloons) and 36 balloons respectively for the entire city.[27]

Secondary targets? Clearing the “fog”

Recollections dim with the passage of time and with such momentous events occurring across Britain on an almost daily basis during the period, it is unsurprising that details sometimes become a little blurred. It is easy with the benefit of hindsight and with access to the plethora of data sources now available, to clear the fog a little and establish an accurate version of events.

Little is still known of the route the JU88 took next or what orders the crew had been issued with. However, the aircraft was next reported at Tilshead in Wiltshire where it is reported to have machine gunned a convoy before heading on to Old Sarum airfield where it reportedly machine gunned the runway.

Tony Clemas who was a child at the time living just outside Salisbury recalls; “Once I heard machine guns firing and suddenly there was a German plane flying just above me. It was firing at a biplane in the distance, it had smoke pouring from its tail as it zoomed out of sight. I learned, later that it shot up several planes on the tarmac at nearby RAF Old Sarum and was itself shot down near the coast.” [28]

In is account Tony Clemas recalls a German plane in combat with a biplane. It is possible that he has become confused between two separate incidents in the same locality during the summer of 1940. At 10.05 on Sunday the 21st of July, exactly three months to the day prior to the JU88 attack on Old Sarum, a Hawker Hart bi-plane with the serial number K6485 was attacked by a Messerschmitt Bf110 C-5 of 4F/14 which was on a reconnaissance flight. The trainee pilot of the Hart, Leading Airman John Arthur Seed, jumped from the aircraft but was killed as a result of multiple gunshot wounds. His aircraft crashed on the Old Sarum airfield near to the Officers Mess. The German aircraft (coded 5F+CM) was later intercepted by Hurricanes of Red Section, 238 Squadron. At approx. 1030 hrs it was brought down at Goodwood Home Farm. The crew of two were captured unhurt.[29] Leading Aircraftman Seed is now at rest at Preston (New Hall Lane) Cemetery, Lancashire.[30]

The captured aircraft, seen below, was taken to the Royal Aircraft Establishment and repaired with parts from another downed aircraft. It was re coded as AX772 and transferred to No. 1426 Flight used for flying demonstrations, finally ending its war at the Central Flying School at Tangmere.[31]

Returning to Tony Clemas’ account of the incident. There was only one aircraft lost at Old Sarum on the 21st of October 1940. This was a Lysander R9128 belonging to 225 Squadron. At 12.25 hrs the plane crashed on take-off killing the Pilot Flying Officer 41559 Daniel Percy Crittal and Sergeant 625563 William Batson who was the aircraft Wireless Operator and Air Gunner.[33] This incident took place over an hour prior to the JU88’s bombing run at Brockworth and therefore cannot be connected. Crittal is buried at Tillshead, Wiltshire where 225 Squadron were based between the 1st of July 1940 and the 29th of July 1941. Batson is buried at Consett Cemetery, Durham.

Also, in his account Clemas stated that the plane shot up several planes on the tarmac at Old Sarum. This was confirmed four days later by the Salisbury Journal who reported; “m/g attack on civilians” – a Nazi bomber venturing on a daylight m/g raid early this week fell victim of an RAF fighter. An aerodrome in the South of England was first m/g’d. One of the ground staff suffered a wound in the lobe of an ear and another a wound in the foot. Then the day raider flying but a few hundred feet up sent a few bursts into a field of dairy cows grazing in a field. None of the animals were touched. Lucky escapes were experienced by men in a field, the bailiff to a well-known firm of farmers, a building contractor and his workmen. A few minutes later, the Nazi, a frantic fugitive from the RAF fighters was shot out of the sky and fell in the same county.” [36]

A reckoning

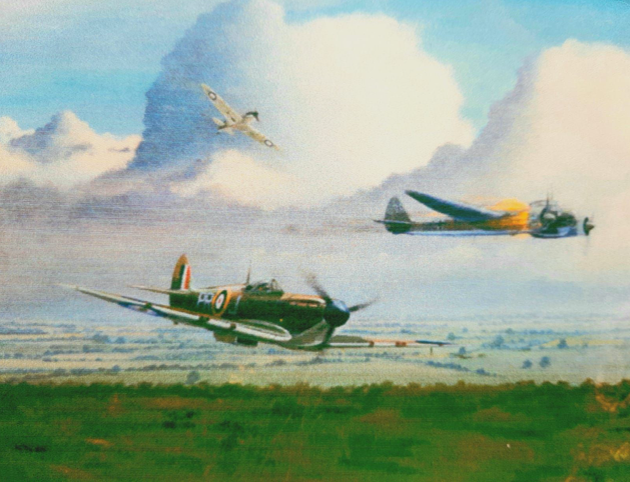

Within minutes of this raid on Old Sarum, two Mark 1 Spitfires from 609 (West Riding) Squadron, Royal Auxiliary Air Force, based at Middle Wallop closed in on the Ju88 and commenced the attack, by this time the bomber was making its way back towards the coast.

The pilots of the Spitfires were Flight Lieutenant Howell and Pilot Officer Hill[37]. Howell was already experienced fighter pilot having been actively involved in the Battle of France and the opening stages of the Battle of Britain. Hill however, had only been with the Squadron for three weeks.

An account of the incident was later recounted by the Squadron Intelligence Officer Frank Ziegler; “the weather on that day was too bad for formation flying by either side. The pilots were informed by their control that a single aircraft posing as a Blenheim had been reported as machine gunning the RAF airfield at Old Sarum at a height of fifty feet. The pilots who were already on patrol, reduced their altitude to approx. 200 feet and patrolled the area between Salisbury and the coast. With the assistance of the Air Controller Flight-Lieutenant Fieldsend they located the aircraft and although partially disguised the original markings were clearly visible. The rear gunner of the JU88 sent out smoke signals to deter the spitfires without success. There followed a pursuit at tree top height.” [38]

The main confrontation occurred over New Milton and resulted in many witnesses one of whom Eric Wyeth Gadd, a teacher from Southampton evacuated with his class to New Milton, wrote a diary during the war years. His diaries were later transcribed into a book “Hampshire Evacuees”. On the 21st of October 1940 he recorded; “At 1.45 p.m. today, sudden noise overhead, followed by a cry from the class, “It’s on fire, Sir” Junkers 88 was passing over school, smoke and flame pouring from its tail. It was at very low altitude and losing height fast. Presently it disappeared into the horizon and clouds of dense black smoke arose. Then a British fighter appeared from nowhere, descended upon the mass of smoke, giving the impression that it would join its victim, repeated this operation then climbed into a “Victory Roll”, All this time the children were agog with excitement, so I did my best to give them a running commentary.

Ten minutes later, explosions were heard which I took at the time to be the Junkers bombs, but I was told later that these were from AA guns firing at a second bomber.[39] The Junkers had fallen in a Swede field at Downton, a few miles away, the crew of five [authors comment – only four dead were ever recorded]. People congregated in such crowds that the Fire Brigade were unable to approach the plane and had to return to their station with nothing accomplished. Will people ever learn to restrain their morbid curiosity? These people ran two risks (a) from the Junker’s bombs (if any); (b) from the second bomber.” [40]

Another witness to the incident, was a pupil at the same school where Gadd was teaching. Leslie R. White who recalls the incident. “…….. it was on that afternoon at Ashley Senior School. The siren had not sounded, but suddenly, as Class 1a was composing anthologies, there was the stutter of machine-gun fire and the roar of engines very low over the school. Outside the classroom windows, blast walls had been erected and it was just possible to see the sky by peering up at an angle from where I sat. Into this narrow band of blue plunged a blazing Junkers 88. I leaped excitedly onto the top of my desk yelling, “It’s a bloody Jerry and he’s all on fire!”. I was rebuked by Miss McLeod but I cannot now remember whether it was on account of my language or my actions”. [41]

The two eyewitness accounts would seem to indicate that the battle was well underway by the time the aircraft were overhead in the Ashley area. This is confirmed in part of the incident coverage as reported by the New Milton Advertiser. ”German Bomber Brought Down in Flames – Crashes in Field between Milton and Milford – Crew of Four Killed

One more German plane will fly no more over England’s quiet villages, bringing destruction in its wake. On Monday, a Junkers 88 was brought down between New Milton and Milford on Sea, crashing into a field of Swedes. The four occupants of the plane were killed.

The owner of the field Mr Phillip C. Thorne of Manor Farm has already had a visit from the Germans when a bomb was dropped in his field a short while ago. Curiously enough, the tail of the bomber was found about a couple of yards from the crater left by the bomb dropped previously.

Mr. Thorne, who was in front of his house at the time, was about 500 yards from where the plane landed in the centre of his field. He stated that the plane was in flames before it touched the ground and one of our fighters was chasing it, machine gunning as it went. Afterwards he heard three reports.

Jack Adlam, a carter, and William Yeates, a farm labourer, with Adlams five-year-old son Robin, were in a field loading mangolds not 100 yards from where the plane fell.

“We heard a terrific noise,” said Yeates, “and then we saw this big aeroplane with flames and smoke pouring from it. We thought it was coming straight for us. One of our fighters was on its tail, giving it terrific bursts of machine gun fire. Before it came down in field it somersaulted, and it was smashed to pieces. We had to hold our horses which were harnessed to the carts being filled with mangolds. One horse, however, took fright; cleared the harness and dashed back to its stable about half a mile away.”

“My little son got under my cart,” Adlam said, “but he soon recovered from the shock and came with us to see the wreckage. We saw no sign of life. Four dead bodies were lying about the ground.”

The military and Police came upon the scene within about ten minutes of the crash and took charge immediately of the bodies and the remains of the plane, which were scattered all over the field. The force of the impact flung one of the engines out of the plane and into a barbed wire fence, tearing it to pieces and winding up the wire like thread.

A large crowd had gathered before the fires were out, and when one of our bombers flew over from the sea towards the wreck the crowd scattered almost immediately, thinking that it might be another German bomber. They returned as soon as they saw that it was one of ours. Among other items, a belt and an automatic were recovered from one of the bodies, and a rubber dinghy with all its apparatus was retrieved.” [42]

The Fire Brigade was delayed in reaching the scene by reason of the dense crowd which gathered about the wreckage.

Like “A bolt from the Blue”

An eyewitness of the actual fight stated that she was cycling along a road near the railway, when suddenly she heard a sound like the rumbling of a train – only much louder and not so regular. A herd of cows which were in the middle of the road at the time began to stampede, and it was with difficulty that the drovers calmed them and drove them quietly into the farm.

Looking across towards the railway she saw the camouflaged wing of one of our fighters dip low over the bridge, and the sudden bright orange flash of gun-fire. There was none of the preliminary whining and swooping that you hear usually during a fight. It was like a bolt from the blue when our fighter let him have it. The German plane streaked away with flames bursting from it, rapidly losing height and disappeared in a cloud of smoke.

Narrow Escapes from Bullets

Some persons in New Milton had narrow escapes from the machine gun bullets that were flying about when our fighter was in hot pursuit of the German bomber, and two men were reported to have been hit.

At the New Milton Hotel, a number of people were playing darts in the lounge when a machine gun bullet pierced the thick glass of the lounge window, leaving a small hole and scattering glass across the room. The bullet passed between two people who had just moved in the middle of a game. At once they all fell flat on the floor and afterwards crawled on “all fours” around the room in a hunt for the bullet. It was found, eventually, by Mrs Moss on the back doormat underneath the staircase. It was an English bullet. A bullet case was also found full of bracken.

A taxi driver did not discover a bullet in the back of his car until he had reached his destination.

Mr J. Moody, the funeral director, who was at the back of his house at the time, and Mrs Moody who was in the passage, were fortunate in dodging a bullet which came through the front casement window in the dining room and went out the side window, lodging in the wood, and the occupants of the flat next door also had a bullet come through their window and found it lodged in the plaster near them.

This bomber crashed less than two miles from where the Messerschmitt 109 was brought down in flames last week.”[43]

Local lad Norman Powell (who was later to join the New Milton Home Guard prior to enlisting in the Army and taking part in the D-Day Landings) recalls the incident; “New Milton took quite a pounding. I was an apprentice joiner for H.H. Drew. We were unloading some timber off a lorry when this German Bomber came roaring over making a terrible noise. It was incredibly low as it came over Drew’s yard, the Spitfire fired all 8 guns and there were bullets everywhere. I was on the lorry at the time, I flew off there and into the workshop and laid down behind some timber. After, we came out we could see smoke rising in the distance, it came down in a field off Milford Road the crew are buried in the church yard at Old Milton.” [44]

Mary Platt’s parents Paul and Nora ran the Bashley Grocery Store and Post Office she recalls the incident; “The bullets hit the front of the building entering every window. Fortunately for us the  [45]dog fight occurred at lunchtime when the shop was shut, and parents were at the back of the house. I was at school, but they told me that there was a sudden frightening noise and they quickly sheltered under the dining table. When it was over, they went onto the shop. There was chaos, bullets had hit cans of soup and bags of flour before entering the wall. There was a scar on the counter and other fittings where bullets had hit the plaster walls making further damage in every room in the front of the house. I still have a book which has a scorch mark where the edge of a bullet grazed the cover. It seems strange that the widows were not broken just small circular holes with small cracks radiating from them, I kept the bullets I picked up in the building for many years but recently took them to the St Barbe Museum at Lymington in an old OXO tin. I well remember seeing the graves of the German airmen in New Milton Cemetery”

[45]dog fight occurred at lunchtime when the shop was shut, and parents were at the back of the house. I was at school, but they told me that there was a sudden frightening noise and they quickly sheltered under the dining table. When it was over, they went onto the shop. There was chaos, bullets had hit cans of soup and bags of flour before entering the wall. There was a scar on the counter and other fittings where bullets had hit the plaster walls making further damage in every room in the front of the house. I still have a book which has a scorch mark where the edge of a bullet grazed the cover. It seems strange that the widows were not broken just small circular holes with small cracks radiating from them, I kept the bullets I picked up in the building for many years but recently took them to the St Barbe Museum at Lymington in an old OXO tin. I well remember seeing the graves of the German airmen in New Milton Cemetery”

The school log for the Milford on Sea Junior school records; “21st of October 1940, Plane brought down in neighbourhood at 1.45.” No further mention of the incident is recorded although many local children were known to have visited the crash site.

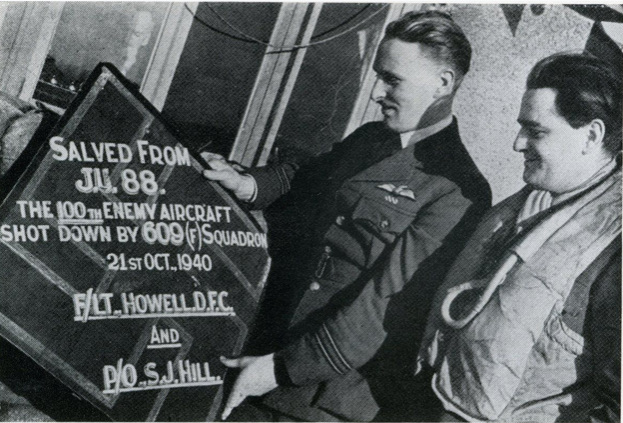

This incident, tragic as it was, marked a milestone for 609 Squadron, they had just become the first Spitfire Squadron to reach 100 enemy aircraft destroyed. Although No 1 (Hurricane) Squadron had already achieved this some months earlier during the Battle of France.

On their return to Middle Wallop, Howell and Hill were required to submit written reports relating to their contact with the enemy. But not before describing the action to colleagues eager to hear the details.

What follows is a transcript of the reports taken from microfiche copies of the original documents held by the National Archives.

21/10/40 Red 1

“I and Red 2 were sent to Portland at 15,000. The E/A[47] had returned South. Controller advised me to stay on patrol. I heard over R/T that one E/A was flying North from base and heard all conversations between Bandy and Blue1. The E/A was reported to be machine gunning Old Sarum at 50ft. I dived down to 200ft and patrolled a position between Salisbury and the coast. Red 2 saw the E/A first, which passed directly underneath us. I was not certain if the aircraft was a Blenheim or a JU88 so I flew alongside to make certain. There was a large black cross on the side of the fuselage, but the rear gunner was signalling with smoke cartridges with no coloured stars. I dived to attack from the rear, and opened fire when the rear gunner had started firing at me. He used red tracer. I broke away at about 40 yds. and saw his starboard motor burst into flames. Red 2 was continuing the attack from astern. The E/A hit the deck and exploded. The Ju88 was never more than ten feet from the tops of the trees. I considered that the controlling was excellent and that the information he gave enabled us to intercept the E/A with comparative ease.” Signed F.J. Howell F/L. [48]

21/10/40 Red 2

“I was on patrol with Red 1, at 200ft, due south of Salisbury. I saw the E/A (enemy aircraft) pass underneath going South. I informed Red 1 who, turned to investigate. Red 1 shouted “Tally Ho” meanwhile delivering an astern attack and firing into starboard motor. As Red 1 broke away I continued to attack from behind and above. I broke away and made two beam attacks after which he hit the ground and blew up. The E/A was never more than 10 feet above the tree tops and was attempting evasive action by diving below the tree tops. The enemy was seen to fire three lots of two smoke puffs, but no coloured lights” Signed S.J. Hill P/O.[49]

“What a Party!”

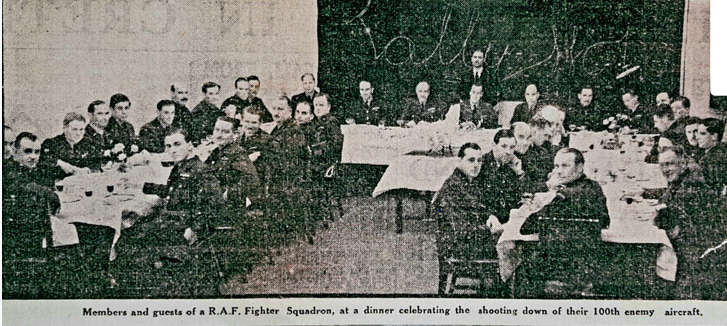

After the formalities of report writing had been concluded, the magnitude of the event took over. The Squadrons 100th confirmed destruction of an enemy aircraft was not only a milestone for the Squadron but a boost to moral for the whole nation, and the press were keen to capitalise on the situation.

“A Yorkshire Auxiliary Air Force fighter squadron has shot down 100 enemy planes, states the Air Ministry News Service. The 100th victim was a Junkers 88 bomber, which was sent plunging earthwards over the South Coast. The squadron has fought with distinction at Dunkirk, in the Channel battles, and the defence of London and the cities of the South and West. Over Dunkirk, nine of the Spitfires shot down in one day four bombers and two Messerschmidt 109s.”[50]

A less formal and certainly less public account of the incident were to be found in the pilots’ logbooks. An entry in Howell’s read; “21 Spitfire X4587 – Patrol Warmwell 15,000’. Overheard on R/T Blue Section chasing E/A North. The E/A machine gunned Old Sarum at 50’. Hill and I patrolled point south of Salisbury. JU88 passed directly beneath us. Followed it under HT cables, and set engine well alight. Hill did beam attack, it crashed wrecked, burnt up. Crew of 4 killed. Landed at Christchurch but not hit”[51]

Hill simply recorded; “21 Spitfire F – Base A.15. J.U.88 destroyed with F/Lt Howell. Crashed near New Milton. Claimed 1/2 destroyed. Squadrons 100 E/A destroyed – What a Party!”[52]

However, for the pilots and ground crew of 609 Squadron far from being a victory party it was a celebration of life, the Squadron took heavy losses both before and after the 21st of October. This was a rare opportunity to distance themselves from the horrors of war and take the briefest of moments to enjoy themselves as young men from diverse backgrounds, brought together for a common cause. And enjoy it they did………!

“About 6.30 p.m. we trooped into the writing room and there found a couple of waiters behind the bar and almost hidden by the large stock of champagne and brandy that had been installed for the occasion. A satisfactory if somewhat boozy party ensured; everybody was in top form and we all felt distinctly pleased with ourselves and life generally. We drank to the C.O., we drank to the Poles, we drank to the squadron, in fact we toasted practically everything we could think of, in round after round of champagne cocktails. It was a very good party!” [53]

“A shocking party in the evening – champagne cocktails of which we all drank many more than we intended. Went to bed feeling very queer & decided the only thing to do was to be sick, which I proceeded to do with gusto. Consequently, next day did not feel so ill. Anyway, we didn’t have to fly much so it was all right.”[54]

“On the 29th I returned to the squadron for the official centenary party, the other one apparently having been unofficial, although nobody would have noticed it………And so on to the party, Great quantities of champagne were consumes; we had an excellent dinner and some peaches, including one from D., which we all cheered to the echo”[55]

In a letter to his fiancee, Gillian Pearce, on the 2nd November 1940, Howell also referenced the party when he wrote; “As to more local news, I have just had the pleasure of shooting down the squadrons 100th enemy aeroplane, It was a JU88 and had been machine gunning an aerodrome. We were about 50 feet. I caught it just over the trees in the middle of the New Forest and after a very exiting chase down valleys, under H.T. cables, missing posts (thank God) and posts by inches, it crashed into a turnip field in an inglorious end, and was completely wrecked. We had a terrific party that evening of champagne cocktails – very potent, very nice.”

“Edelweiss” in Milford on Sea

Whist celebrations and congratulations were in full swing at the squadrons Middle Wallop base, the wreckage of 9K+BH remained in situ at Downtown Manor Farm.

Such a significant event in a small wartime village undoubtedly caused a great deal of interest and many visitors attempted to reach the site of the crash near Blackbush. The aircraft was however almost completely destroyed, with debris spread over a wide area of farmland. Concerns remained that live munitions within the wreckage were still a danger and a cordon was placed around the crash site enforced by local police officers and the Home Guard.[57] However, despite the dangers and government legislation about removing items from crashed aircraft some visitors to the site were able to secure mementos.

Mike Bowers was at the time serving as a Corporal with the Devonshire Regiment and billeted in Horde House School. He was one of those who visited the crash site and recalls; “I remember looking inside the cockpit and picking up the belt. I pulled off the leather and rescued the aluminium buckle covered in bloodstains.”[58] Years later Mike donated the buckle to the St. Barbe Museum in Lymington.

Another Milford resident “gifted” a memento of the crash was Pamela Stone (later the wife of Milford Policeman – PC Thomas Richard (Dick) Coates who served the village between 1954-1956). As a young woman Pam was presented with a clear ring fashioned from Perspex from the cockpit screen of the stricken aircraft. She kept the ring for many years but sadly lost it during a visit to Bournemouth Tennis Club, the ring fell from her finger, through the wooden seating and down to the ground underneath the stand, never to be recovered. [59]

As with all such events on English soil, the wreckage was the subject of a thorough examination by representatives of the Air Ministry seeking some intelligence or an insight into the workings of the Luftwaffe to give the RAF the advantage. The wreckage of 9K+BH was no exception.

The first record was submitted to the War Room (Air Ministry) in Whitehall 25th October 1940; “Confirmation of enemy aircraft brought down – JU88 crashed 21.10.40 near New Milton, ref U6715. Identification markings – somewhat confused. 9k+BH (9K in black, BH in White). Works No. Of airframe on fin 8116. Engines – 2 Jumo 211. Cause of crash fighter action. Strikes from stern and beam, starboard engine on fire. Aircraft smashed and burnt out except tail unit. Armament appears standard, difficult to ascertain exactly owing to sate of machine. Crew – 4 dead. Enemy machine reported to have dropped grenades during action. Samples of flare or grenade recovered from wreckage (report later).”[61]

A slightly more detailed report followed; “Report 3/116 – Ju.88 A1 – crashed on 21/10/1940 at 13.30 hours at New Milton, map reference U6715, Identification markings are not clear. 9K in black paint are probably old markings appear in front of the cross followed by BH in white. Airframe made by Norddeutsche Dornier Werke: Werke Nr. on fin 8116. Engines: Jumo 211. Following fighter action starboard engine was on fire and aircraft made a crashed landing and, with the exception of the tail unit burnt out. A number of 303 strikes from astern and the beam have been found in the wreckage not burnt. Parts of several machine guns found but position not known. A few plates of armour found in wreckage, but position cannot be fixed. Three articles 7-3/4” long by 2-1/8” diameter fitted with stick at end and propeller in nose, found in wreckage. These appear to be grenades, or some type of flares and they are being further examined. Crew of 4 killed.”[62]

Following the official crash investigation, 609 Squadron ground crew recovered several undamaged items as souvenirs most notably the tail fin which was later inscribed with the words “SALVED FROM JU88. THE 1OOth ENEMY AIRCRAFT SHOT DOWN BY 609(f) SQUADRON. 21ST OCT 1940. F/LT HOWELL DFC AND P/O S.J. HILL”. The tail fin was to remain hung on the wall of the squadron’s dispersal huts until 1944, its current whereabouts is unknown.

Many of the 609 Squadron pilots were keen to have their photograph taken with the memento. Sadly, many of them would not live to see peace return to their homeland.

The Lord is my Shepherd

Three days after the crash, the Luftwaffe crew were laid to rest at New Milton; “German Airmen’s Funeral – R.A.F. accord full military honours. The funeral of the four young Nazi airmen who were killed when their Junkers 88 crashed on a farm near Milford-on-Sea on Monday week after being shot down by a British fighter, took place in the Parish Churchyard at New Milton on Thursday, full military honours being accorded. Aircraftmen acted as bearers, and with the guard of honour and firing party there were in all about forty R.A.F men attending the ceremony. The Church of England Service was read by the Rev. T.H. Bowen, one of the parish’s curates and included the reciting of the 23rd Psalm. “The Lord is my Shepherd.” The coffins were draped with swastika flags, the emblem being in dark blue on a white ground, and the flags were removed when the coffins were lowered into a common grave in the presence of many onlookers, mainly women and children. Wreaths of carnations, chrysanthemums and other autumn flowers were sent by the Commanding Officer, the Officers, the NCO’s and the Aircraftmen at a Royal Air Force Station.

The dead airmen, whose remains were conveyed from the mortuary to the churchyard on an RAF lorry were aged 25, 23, 22 and 21 and their coffins each had a plate bearing the name and age with the date of death.” [66]

A local response

The week following the crash local papers were littered with letters and other comments from local residents relating to the crash.

“A Readers Protest – Sir,- I am sure many people in Lymington and still more so those recently and tragically bereaved in New Milton[69] must have read with indignation and disgust your account of the proceedings at the funeral of the four Nazi airmen. Money spent on the swastika flags and wreaths of carnations would have served better purpose if it had been given to the Spitfire Fund. As to the use of Psalm -” The Lord is my Shepherd”- the least said the better. It may be as well to recall the words uttered by the captain of the Emden in the last war when magnanimously handed back his sword by his captors: “ You Englishmen are gentlemen, but you are fools.” [70]

The following week in the same paper Notes and News by “Townsman” read;

The Siren Question – The siren in question seems to require overhauling. At present it appears to shriek when no bombs drop to be silent when danger is right overhead. For instance, in the scrap last week, no siren went, and two men were injured from flying bullets, one of whom is reported to have died since.[71]

A Brilliant Effort – That fight last week was a brilliant individual effort, in which a lone British fighter brought down a lone German bomber. It was such an outstanding success that a full report of the British pilot’s tactics should be called for and passed onto other pilots. It seemed that he knew the weak spot of the bomber- and knew how to strike it. Nobody can say for certain, but it appears that his bullets killed the pilot if not the others in the plane, so that it glided down to earth in flames with the dead pilot at the controls.

Exhibition at Christchurch – At the same time, I am glad to see that Mrs S.G. Barber of the King’s Arms Hotel, Christchurch, by hook or by crook, has got hold of a parachute and some relics of an enemy plane brought down near New Milton, and is holding an exhibition of the parachute and the wreckage in the ballroom of his hotel from 11 am – 10 pm, devoting the minimum charge of admission of 1s. (6d. Children and those in uniform) to the New Forest Spitfire Fund. The parachute is stretched over the room, in which there are over 50 yards of pure silk and some 100 yards of silk cord. This is being raffled, and these proceeds are also being given to the New Forest Spitfire Fund.

A rubber boat given to Mr. Barber is also among the exhibits, and this is to be sold by auction at the Spitfire dance, which is to be held in the ball room on November 9th, from 8 pm to 12.

No doubt many of our readers will visit the exhibition, but I regret that it was not possible to arrange a similar exhibition in Lymington and throughout the New Forest.

Mr. Barber is to be congratulated on his enterprise, which he tells me has cost him a lot of time and much money.”[72]

Another week on and local residents had time to reply to the initial letter criticising the manner in which the funeral of the four airmen was conducted. On the 9th of November, the following two letters appeared.

“A Natural Protest – But – Sir, – Your “Reader’s Protest” with regard to the funeral of the Nazi airmen was a very natural one, but it seems a pity not to look at the wider view. If the RAF chose to honour the dead enemy is that not in keeping with British tradition? Would we not all prefer to be “gentlemen and fools” rather than copy Nazi methods. The use of the 23rd Psalm reminds us of the wideness of God’s mercy – we dare not pray for mercy for ourselves, and justice for our enemies, and we must remember men like Pastor Niemoller in the prison camps in Germany who are fighting for the same spiritual freedom – and we trust in God for the future and deep humility we should try to thank Him “that he has watched was with this hour.” [73]

” RAF Tribute to Nazi Airmen – Sir,- May I once again have a little space. In your issue of the “advertiser” is a letter from, ________ who seems disgusted at the kindly, and Christian thoughts and actions of the authorities in the burial of four Nazis. May I make a suggestion? Many of us will agree that this war is being waged both spiritually and also, to our sorrow and knowledge, materially: i.e. Good over Evil things. We all know the Power of Good is greater than that of Evil, and that Good will prevail. This being so, then anything that we may SAY or DO, that is kindly and “of good repute”, is another link, or links, in the great chain of goodness. Thus, weakening the power of evil, until finally by our patience and by our “sacrifices” that we may be called upon to offer, even if it means offending one’s own ideas and ideals, we have a kinder humane world.

For myself, and I think many will perhaps agree, the action of “our” airmen and authorities concerned in the case of the Nazis, shows a very true example of Goodness. The actions are set as an example, by the very men who helped in the destruction of the enemy.

Our brave RAF are setting us all examples that we cannot hope to follow; – let us therefore try and follow them in this act, in which we can follow if we will. But so doing we are not dishonouring our dead, be they civilian or Forces.”

As recorded in the local papers account of the incident the airmen were buried in the Churchyard at St Mary Magdalene, they were laid to rest in plot 1 area C. They remained there until the 20th February 1963 when they were re-interred at the German Military Cemetery, Cannock Chase in Staffordshire.

We will Remember them

609 Squadron

Frank Johnathon Howell

[74]Frank Johnathan Howell, was born at Golders Green in London on 25th January 1912. He took a short service commission in the Royal Air Force in 1937, obtaining his “wings” and being promoted to Flying Officer on the 1st September 1939, and on the 14th of November Flying Officer Howell he was posted to 609 (West Riding) Squadron at Drem.

[74]Frank Johnathan Howell, was born at Golders Green in London on 25th January 1912. He took a short service commission in the Royal Air Force in 1937, obtaining his “wings” and being promoted to Flying Officer on the 1st September 1939, and on the 14th of November Flying Officer Howell he was posted to 609 (West Riding) Squadron at Drem.

The squadron moved considerably during the early months of the war. Frank of course followed with postings to Kinloss, Drem, Northolt Middle Wallop and finally to Warmwell on the 29th November, although half the squadron were operating at Warmwell for some weeks prior to this.

Frank saw active service in supporting the withdraw of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) from Dunkirk in May 1940. He was shot down whist in combat with a Junkers 88 off the Dorset Coast, on the 18th July 1940. Despite ditching in the sea, he was recovered unhurt by a Royal Navy vessel.

Four days after the incident on 21st October, Frank was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC). The citation read; “This officer has shot down four enemy aircraft, has been partly responsible for the destruction of five more and has damaged several others. He has led both the squadron and his flight with skill and determination, which have undoubtedly contributed greatly to recent successes. Flight Lieutenant Howell’s keenness and energy combined with his courage and leadership in many combats have set a splendid example to the rest of the squadron.”[75]

On the 20th February 1941 Frank was posted to Filton near Bristol as the newly formed 118 Squadrons Commander. During his command of 118 Sqn, Frank won a bar to his DFC. “The King has approved the following awards in recognition of gallantry displayed in flying operations against the enemy:- Bar to DFC: Acting/Sq Ldr. F. J. Howell, D.F.C. 118 Sqn. This officer has displayed fine qualities as a fighter pilot, combined with outstanding leadership and talents for organisation. He has played a large part in raising and maintaining a high standard of efficiency in his squadron, which had distinguished itself. He has destroyed at least ten enemy aircraft and possibly a further seven.”[76]

Frank found himself on the battleship Prince of Wales when she was sunk on the 10th December 1941 with the loss of 890 hands. Having survived the sinking, he was taken prisoner or of war by the Japanese. After the war Frank remained in the RAF and was in command of a 54 Squadron equipped with Vampire aircraft. On 9th May 1948, Frank was making a cine film of his squadron’s aircraft, when the wingtip of one of them struck him, severing his jugular vein causing fatal injuries.[77]

Sydney Jenkyn Hill

[78]Sydney Jenkyn Hill was born in Briton Ferry, South Wales on the 27th April 1917[79], although his family later moved to Ferndown, Dorset.

[78]Sydney Jenkyn Hill was born in Briton Ferry, South Wales on the 27th April 1917[79], although his family later moved to Ferndown, Dorset.

He was educated at Uppingham School in Rutland between 1931 and 1935 and whilst studying at Constables House[80] took an active part in the Uppingham OTC attaining the rank of Lance Corporal[81].

Sydney’s further education was conducted at Imperial College London, where he studied Metallurgy at the School of Mines. Whilst at university he continued his passion for flying training on Avro Tutors and the Hawker Hart as a member of the University Air Squadron.

Sydney enlisted into the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve on the 7th March 1940, initially posted to No. 6 Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS) in Sywell, Northamptonshire. During this initial period of training Sydney was raised to the rank of Pilot Officer on probation on the 26th March 1940. He continued his training at No. 10 EFTS at RAF Yatesbury, Wiltshire[82].

His final training posting was to No. 7 Operational Training Unit (OTU) based at Hawarden, near Chester on the 7th September 1940.[83] Formed in June 1940, 7 OTU provided training in single seat fighters, initially intended to train pilots in the operations of both Spitfires and Hurricanes, by August 1940, during Sydney’s time with the unit, it was training solely on Spitfires.

Sydney’s first operational posting was to 609 Squadron on the 30th September 1940. He soon became a popular member of the Squadron, Wing Commander Paul Richey described Sydney in his diary as “a trifle overweight, with thick black hair, but always had a smile on his face”[84]. Two weeks after his arrival, on the 16th October Sydney was confirmed in rank, becoming Pilot Officer 77795 Sydney J. Hill.[85]

On 4th June 1941, Sydney’s best friend within the Squadron, Flying Officer Johnnie Curchin was killed in action[86]. Sydney lost his smile and according to the squadron biography became “bent only on revenge”.[87] Then, during the late afternoon of the 18th of June 1941, Hill was taking part in Circus 15. Six Blenheim bombers of 107 Squadron based at Great Massingham, Norfolk took off and headed towards their target of Bois de Liques, they were escorted by fighters from 1, 258 and 312 Squadrons, providing a close escort. Further fighters from 145, 303, 610 and 616 Squadrons provided high cover with 92 and 609 Squadrons forming part of the Target Support Wing.

German fighters of Jagdgeswader (Fighter Group) 26 intercepted the raid very early on, choosing to engage the high cover first. Oberstleutnant Adolf Galland claiming one of the spitfires shot down. With the high cover committed further fighters attacked the bombers and their close escort but were met with a spirited defence.

Once the bombing raid had been successfully completed the formation turned for the coast and home, all six Blenheim returned safely. The German fighters continued to harass the formation well into the channel. Sydney along with a Belgian pilot, Baudouin de Hemptinne engaged vastly superior numbers of the German Bf109 fighters off Gap Griz Nes, his aircraft, a Spitfire VB W3211 ‘H’ was severely damaged during the engagement. Despite the damage, Sydney managed to reach the English coast but sadly crashed five miles outside of Dover.

A fellow pilot John Bisdee recalled; “Syd tried to get back despite being advised to bail out. He thought he could make it and very nearly did. He just failed to get over the coastal cliffs, the Spitfire falling in flames onto the beach below. The pilot was incinerated. His family asked to have his ring, but it had melted in the heat.

At his funeral, as the party was moving to the cemetery, it had been arranged for two Spitfires to fly low, in salute. Two aircraft duly arrived but they turned out to be two ME 109s. Everyone scattered, leaving the coffin in the middle of the road.”[88]

Sydney Jenkin Hill, one of “The Few” is buried at Hawkinge Cemetery. He was just 23 years old.

Spitfire VB W3211

Sydney Hill lost his life in a Spitfire mark VB with the serial number W3211, the aircraft bore the name “Norman Merrett”. So just who was Norman Merrett and why was his name on this Spitfire?

As the Second World War progressed, and the losses of battlefield equipment mounted, there was a desperate need to raise funds in order to purchase more weapons to continue the war against Germany and her allies. “Presentation weapons” were seen as a way that the civilians could directly contribute to the war effort by raising money to purchase such items. Similar schemes had been popular during the Great War where presentation tanks and aircraft were provided as a result of public subscription.

A “price list” was made out that £5,000 would purchase a single-engine fighter, £20,000 a twin-engined aircraft and £40,000 for a four-engine aircraft.

Born on the 12th October 1912 in Penarth[91], Norman Stuart Merrett was the only son of a wealthy industrialist, Sir Herbert H. Merrett of Michelston-le-Pit in South Wales. Norman was educated at Newnham, Summerfield’s, Oxford and Clifton colleges before joining the family firm Gueret, Llewellyn and Merrett in 1931. The company was well established in the coal industry.

Even before the outbreak of war, Norman was a keen aviator, gaining a licence to fly the DeHaviland Gypsy Moth in 1936, flying from the Cardiff Flying Club. He was also a member of the Auxiliary Air Force serving with 614 (County of Glamorgan Squadron).[92]

[93]On the 10th August 1940, now on active service the squadron were based in Scotland. Whilst on a training flight in a Lysander aircraft, practicing evasive manoeuvre techniques, Norman was involved in a head-on collision with another aircraft from the same squadron. Norman and his gunner Flying Officer James Ferguson Harper were killed. The pilot of the second aircraft survived. Norman was returned to his hometown for burial.

[93]On the 10th August 1940, now on active service the squadron were based in Scotland. Whilst on a training flight in a Lysander aircraft, practicing evasive manoeuvre techniques, Norman was involved in a head-on collision with another aircraft from the same squadron. Norman and his gunner Flying Officer James Ferguson Harper were killed. The pilot of the second aircraft survived. Norman was returned to his hometown for burial.

Within 10 days of his son’s death Sir Herbert Merrett has sent a cheque for £5000 to the Minister for Aircraft Production for the purchase of a Spitfire, the money being raised by the 100 residents of Michelston-le-Pit in Normans memory.

The letter accompanying the cheque read; “On Sunday last we received the tragic news that my son Flying Officer Norman Merrett, had lost his life somewhere in Britain whilst serving with the R.A.F. On Monday morning we woke to find that, as a result of a raid, five of our cattle had been killed and others badly maimed. The village in which we live is one of a thousand acres and a population of a hundred people. These tragic circumstances have served only to strengthen the determination of this little community to prove to the despicable enemy that we have set our hearts to rise to the greatest possible heights in assisting you and your colleagues in the admirable efforts you are making to defend and feed the people of the most sacred spot on God’s earth. I cannot provide you with another gallant son. The one who has gone was my only son. But I want you to accept from the village of Michelston-le-Pit the enclosed cheque for £5,000 to purchase a Spitfire, so that one of the ever-growing number of lads from Britain and the Dominions, so anxious to defend us in the air, may be equipped with an instrument which, combined with that indomitable spirit, courage and fearlessness will enable him, as his colleagues are now doing to serve toll of those inferior beings attempting, with increasing failure, to demolish the morale of our people. Every member of the community is subscribing towards the Spitfire. It is not a personal gift, but something from us all to commemorate the passing of my son,”[94]

And so, Spitfire W3211 “Norman Merrett” was constructed and first flew on the 14th of May 1941, it was passed to No. 8 Maintenance Unit two days later. On the 16th May 1941 it was delivered to 609 Squadron and coded PR-H. The aircraft had only completed 28.35 flying hours when it was shot down resulting in the death of Sydney Hill.

Kampfgeswader (Edelweiss) 51

Kampfgeswader (bomber wing) 51 was created on the 1st May 1939, formed from the re-designated KG 255. The training and mobilisation of the group was completed on 20 August 1939 and it was redeployed to Memmingen. KG51 took part in almost every air campaign of the war suffering heavy losses. The wing was given the name Edelweiss by Herman Goering who named several bomber wings after Alpine flowers.

Sadly, the loss of 9K+BH was just another loss for the wing and consequently little is recorded about the aircraft or its crew. In writing this account we will ensure that their names at least will not be forgotten.

Oberleutnant 65103/3 Max Joseph Fabian, the pilot and most senior member of the crew, was born on the 13th of October 1915 in Loeben.

Unteroffizier 65103/27 Ernst Wilhelm, the Wireless Operator and youngest member of the crew, was born on the 17th of February 1919 in Kehl.

Unteroffizier 65103/36 Max Scholz, the Observer, was born on the 29th of May 1917 at Myslowitz-Tarnowitz a small town in Southern Poland.

Gefreiter 65103/37 Franz Stadelbauer, the air gunner, was born on the 23rd of January 1918 in Nürnberg.

All four now lay at rest at Cannock Chase German Military Cemetery, Staffordshire.

A final word

Eighty years on and it is easy with the benefit of hindsight, to judge these men and their actions. The world in the 1940’s was however, a very different place and many of those who wore a uniform, regardless of colour, were doing so not through choice but were compelled to do so by those in a position of authority.

Today we face different challenges, our opponents do not wear a uniform. However, in the same way we battle daily with crime, terrorism, famine and disease. As a community now, as then, we stand together, stronger in times of adversity.

War has touched all our lives in some way and, as a community, together in the spirit of compassion and reconciliation we remember all those who have lost their lives a result of war. We also remember the loss suffered by their families and loved ones and hope to never to experience such events again.

“A nation that forgets its past has no future” – Winston Churchill.

Bibliography

In researching this account of the following publications and sources of reference have been of great assistance.

Crook, D (1942) Spitfire Pilot

Dierich, W. (1975) Kampfgeswader Edelweiss – The history of a German bomber unit 1930-1945

Foreman, J. (1994) 1941 Part 2 The Blitz to the non-stop offensive – The Turning Point

Franks, N.L.F (1997) RAF Fighter Command Losses Vol 1 1939-1941

Gill, P. (1995) South Gloucestershire at War

Goss, C. (1994) Brothers in Arms

James, D. (1994) Gloucester Aircraft Company

Haberlen, K (2001) A Luftwaffe bomber pilot remembers

Mason, F.K. (1969) Battle over Britain

Priddle, R (2003) Wings over Wiltshire

Ramsey W.G. (1980) The Battle of Britain – Then and Now

Ramsey W.G. (1988) The Blitz – Then and Now Vol 2 – After the Battle

Rennison, J. (1988) Wings over Gloucestershire

Richey, P (1993) Fighter Pilot’s Summer

Wynn, K.G. (1989) Men of the Battle of Britain

Zeigler, F. (1971) Under the White Rose – The History of 609 Squadron

- Artwork – M.A. Kinnear. ↑

- Stanley, J. The Exbury Junkers, A World War II Mystery 2004. ↑

- This is the figure most quoted post war, although conflicting accounts do exist. ↑

- Balke, p.176 ↑

- James, D. Gloucester Aircraft Company 1994 p. 8 ↑

- James, D. Gloucester Aircraft Company 1994 p. 13 ↑

- The Gloucester Archives ↑

- James, D. Gloucester Aircraft Company 1994 p. 21 ↑

- Pilot Officer Charles ‘Alec’ Bird – Wings over Gloucetsershire ↑

- South Gloucestershire at War P. Gill. P.30. ↑

- Battle of Britain Weather Diary ↑

- JU88 9K+BH somewhere in France, Summer 1940 with ground crew. Authors collection. ↑

- Royal Observer Corps Records – Log Book 21, Group 3 – Hampshire Archives ↑

- Memoir Colonel, Sir James L. Sleeman – “The veil is lifted” – David Hedges. ↑

- Document D9755/1.- Gloucestershire Archives ↑

- Mrs Nita Spires – letters to the author 22/09/2007 & 03/09/2007 ↑

- Mrs Peggy Allews – letter to the author 15/08/2007 ↑

- Bridgeman P. Enemy action in and round Hucclecote 1940-42”– D0846/7/2 – Gloucester Archives ↑

- Photograph – Jane Field on behalf the late Hilda Lowe. ↑

- Photograph – Olive Stinchcombe. ↑

- Olive Stinchcombe, niece. Letter to the author 16 September 2007. ↑

- Photograph – Author’s collection ↑

- South Gloucestershire at War P. Gill. P.30. ↑

- Ivor F. Eeles. Letter to the author 11 August 2007 ↑

- Ivor F. Eeles. Letter to the author 31 August 2007 ↑

- AA Command – Colin Dobinson p. 519. ↑

- Peter Garwood – Barrage Balloon Reunion Club. ↑

- BBC People at war – A3555399 21 January 2005 ↑

- The Blitz then and now Volume 1 p144. ↑

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission. ↑

- Imperial war museum – HU 93008. ↑

- Royal Air Force ↑

- Commonwealth War Graves Commission ↑

- Westland Lysander – 225 Squadron, Old Sarum, November 1940, similar to that flown by Critall. ↑

- Grave of Danial Percy Crittall, Authors collection ↑

- Salisbury Journal 25th October 1940 ↑

- Hill was flying Spitfire X4590 which is currently on display at the RAF Museum at Hendon. ↑

- Zeigler F.H. The Story of 609 Squadron – Under White Rose p, ↑

- no second bomber was ever recorded ↑

- Gadd E.W. Hampshire Evacuees – p.53 ↑

- White L.R. – The Lure of the Blue p. 13 ↑

- New Milton Advertiser – 26th of October 1940 ↑

- Referring to the crash of Bf 109 in Everton – 15/10/1940 Geft. Pollack taken prisoner. ↑

- Powell N. – Verbal account to author 2003. ↑

- Photograph – Authors collection. ↑

- 609 Squadron Association. ↑

- E/A – Enemy Aircraft ↑

- The National Archives ↑

- The National Archives ↑

- Yorkshire Post – 4th November 1940 p.1 ↑

- Extract from Howell’s logbook. Authors collection courtesy Jennifer Dexter – Daughter. ↑

- Extract from Hill’s log book. Authors collection courtesy Mary Adams – Sister. ↑

- Crook D. DFC – Spitfire Pilot p. 190 ↑

- Bisdee J. Battle of Britain diary 21 Oct 1940 – www.rafmuseum.org.uk ↑

- Crook D. DFC – Spitfire Pilot p. 192 ↑

- Southampton Daily Echo 4th November 1940 p.7 ↑

- The Home Guard had previously been called Local Defence Volunteers. Prime Minister, Winston Churchill changed the name of the organisation on the 23rd August 1940, coincidentally the day that New Milton was bombed for the first time. ↑

- New Milton Advertiser and Times – undated extract. ↑

- Pam Coates – Verbal account to the author 2007. ↑

- JU88 9K+BH somewhere in France, Summer 1940. Authors collection. ↑

- Whitehall Air Ministry briefing note dated 25th Oct 1940. ↑

- Crashed enemy aircraft report No.14 25th October 1940 ↑

- 609 Squadron Association ↑

- News Chronicle Nov 1940. ↑

- 609 Squadron Association ↑

- Western Gazette 1st November 1940 ↑

- Peter Foote archive. ↑

- Grave site in 2006 – Authors collection ↑

- New Milton was bombed on the 23rd of August 1940 with the loss of 23 lives. ↑

- New Milton Advertiser and Times – 2nd November 1940 ↑

- No records of local casualties have been traced. ↑

- New Milton Advertiser and Times – 9th November 1940 ↑

- New Milton Advertiser and Times – 9th November 1940 ↑

- Photograph – Jenifer Dexter – Daughter. ↑

- The London Gazette of 25th October 1940, Issue 34978 ↑

- The London Gazette of 16th December 1941, Issue 35383 ↑

- Wynn K.G. Men of the Battle of Britain p. 201 ↑

- Painting of Hill – Mary Adams – Sister. ↑

- Hill, S.J. RAF Service Record ↑

- Uppingham School Roll 1900-1972 ↑

- Hill, S.J. RAF Service Record ↑

- Hill, S.J. RAF Service Record ↑

- Hill, S.J. RAF Service Record ↑

- Richey P. Fighter Pilots Summer p. 84 ↑

- Hill, S.J. RAF Service Record ↑

- Wynn K.G. Men of the Battle of Britain p. 189 ↑

- Zeigler F.H The Story of 609 Squadron – Under the white rose ↑

- John Bisdee Dairy – The National Archive ↑

- 609 Squadron Association ↑

- Authors collection ↑

- Chris Gridley – nephew. ↑

- Western Mail 23 August 1939 p.8 ↑

- Photograph Chris Gridley – nephew. ↑

- Wings of Victory – Tributes from the many to the Few p. 194 ↑

- Photographs – Chris Gridley – nephew ↑

- Photographs – Authors collection ↑